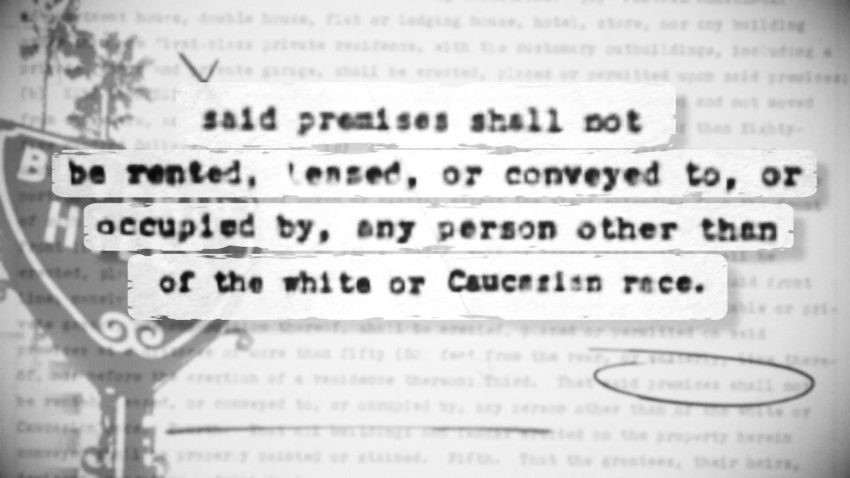

Buried deep in the small print of deeds to a home that sold recently in this ritzy city lurks this stunning caveat: “Said premises shall not be rented, leased, or conveyed to, or occupied by, any person other than of the white or Caucasian race.”

That is known as a racial covenant. And though now illegal, language like it still exists in the deeds to homes all across the United States.

“Pretty much every community in the country is going to have racial covenants,” said historian Kirsten Delegard, a founder of the Minneapolis-based Mapping Prejudice project, which researches the covenants that barred nonwhites from buying property in the city’s most desirable neighborhoods.

“Every city, large or small, that I’m aware of, where anybody has looked for racial covenants, they have found them.”

The practice began in the 1920s. And for nearly 50 years, developers and realtors wrote racial covenants into the deeds of millions of new homes.

Federal law eventually banned the practice, but changes to laws in every state and laborious legwork – searching through millions of documents – would be required to expunge the exclusionary language. So, it remains in property records, shocking some would-be sellers and buyers who stumble across it.

Now, debate simmers over whether racial covenants should be removed. Some experts warn that hiding the mistakes of the past could stymie efforts to somehow make amends and compensate communities of color that still feel the economic hit of being denied access to lucrative property ladders.

“We need to know where these restrictions were put in place if we’re ever going to dismantle the system of racism in a logical, consistent way,” Delegard said.

But others, including those whose forebears were targeted by racial covenants, say it’s time for the insidious language to vanish for good.

“We don’t need to maintain that language in a document to understand the history of where we’ve come from,” said Nikole Hannah-Jones, founder of The 1619 Project, which aims to reframe American history by including the contribution of black Americans.

“It is akin to leaving up in the South, where you had Jim Crow laws, keeping up the ‘no coloreds’ or the ‘white only’ signs at water fountains, bathrooms, other facilities and saying, ‘Oh, just ignore the sign. You can drink out of either one. Just ignore it,’” said Hector De La Torre, a former state lawmaker in California. “That’s what this is.”

Nonwhites welcome only as ‘servants or employees’

De La Torre, whose parents moved to the United States from Mexico in the 1960s, now lives in a house in South Gate, California, that still has a racial covenant clause that at one time would have barred him from living there.

“I paid very good money for this house,” he said. “And this has to come along with it? It’s ridiculous.”

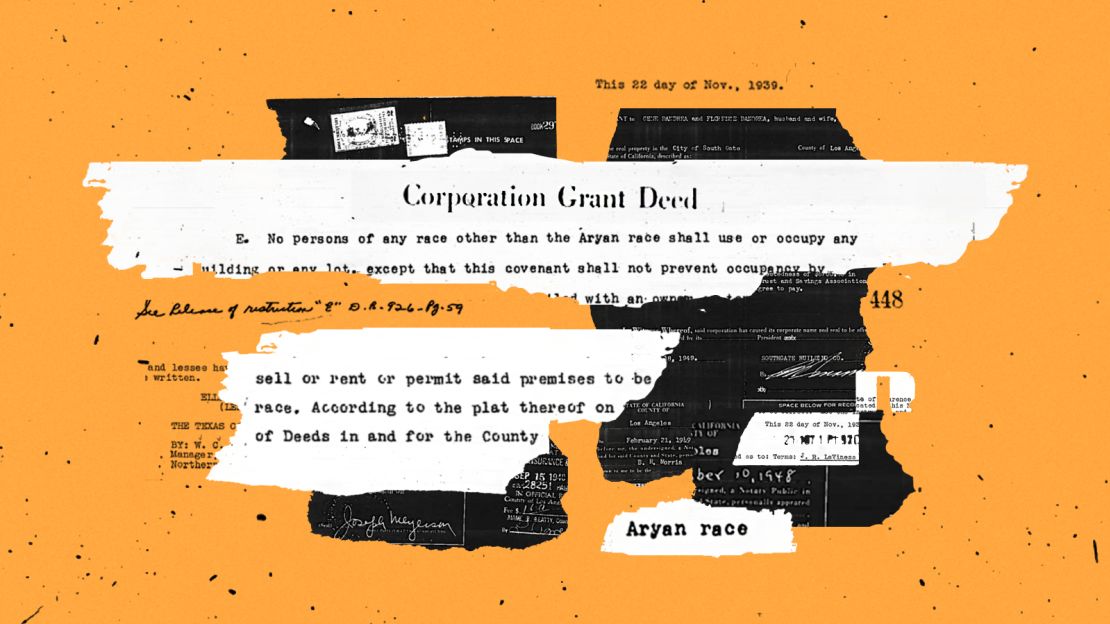

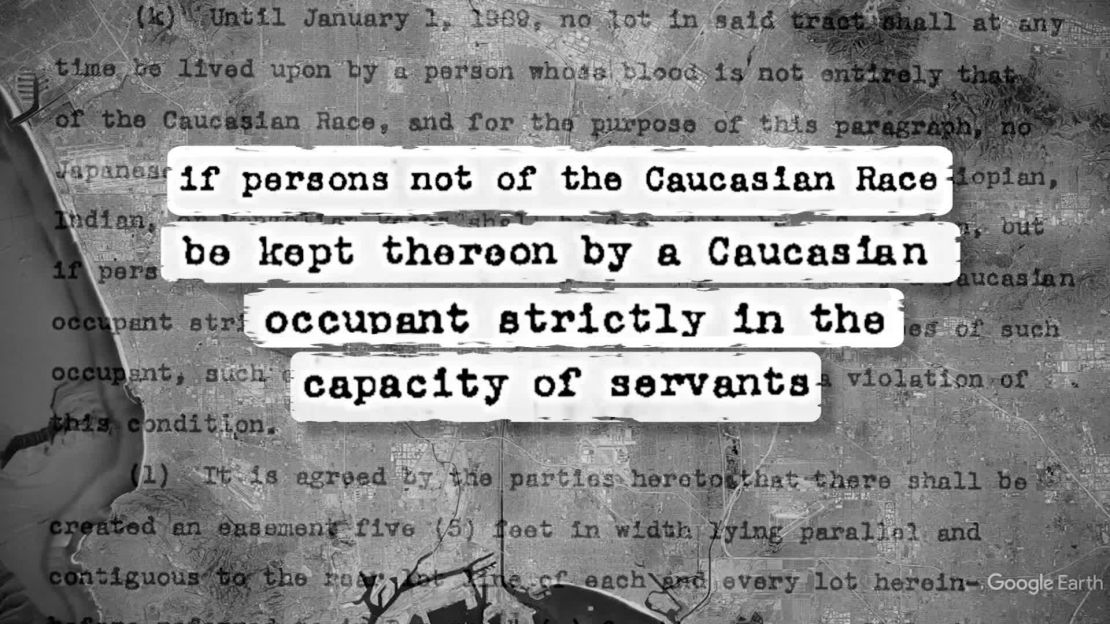

De La Torre’s deeds do include one notable exception to the “Caucasians only” clause: “If persons not of the Caucasian race be kept thereon by a Caucasian occupant strictly in the capacity of servants or employees of such occupant such circumstances shall not constitute a violation.”

Sitting in the kitchen, De La Torre offered his take: “So, perfectly fine for us to be servants and ‘kept’ in these houses. But could not own it, … could not live in it.”

De La Torre in 2008 pushed a bill that would have removed deeds’ racist language every time a home was sold in the state. During that push, The Los Angeles Times reported, “The bill has run into stiff opposition from real estate agents, title insurance companies and county recorders who complain that it would be expensive and create a bureaucratic nightmare that could slow real estate transactions – to little purpose since the covenants are already illegal.” Then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger praised De La Torre’s efforts but vetoed the bill.

Indeed, striking the language of racial covenants is no simple task. Erasing every such reference would be laborious, time-consuming and, therefore, expensive. “We’ve looked at between 10- and 15-thousand deeds, individually,” said Sarah Shoenfeld, who co-founded Mapping Segregation in Washington, D.C. “And that only covers a very small portion of what needs to be done.”

And before any of the offensive language could be erased, lawmakers in each state would have to change the law to allow the alteration of these historic documents.

In some places, official records can now be amended to account for racial covenants. In Washington state, Minnesota and California, homeowners can ask county clerks to attach a “modification document” to deeds stating that the offensive covenant is now illegal. And real estate professionals in California who send deeds that contain racist language to clients must include a cover sheet that states – in 14-point, boldface type – that a modification can be filed.

But still, the original language remains.

Searching through documents from the Beverly Hills neighborhood of Asheville, North Carolina, Drew Reisinger, register of deeds in Buncombe County found the same “Caucasians only” language as in the deed from the tony California city that shares its name.

In the deed to his own Asheville home, Reisinger unearthed this passage: “The land and buildings shall not be leased or sold or conveyed to a negro or any person of any degree of negro blood or any person of known bad character.”

“In North Carolina, there isn’t a mechanism to remove anything from the record,” he said. “It’s horrific. … There’s no way to read that that doesn’t make your stomach churn.”

Racist language was meant to sound official

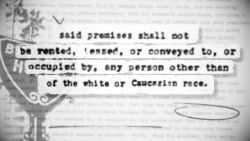

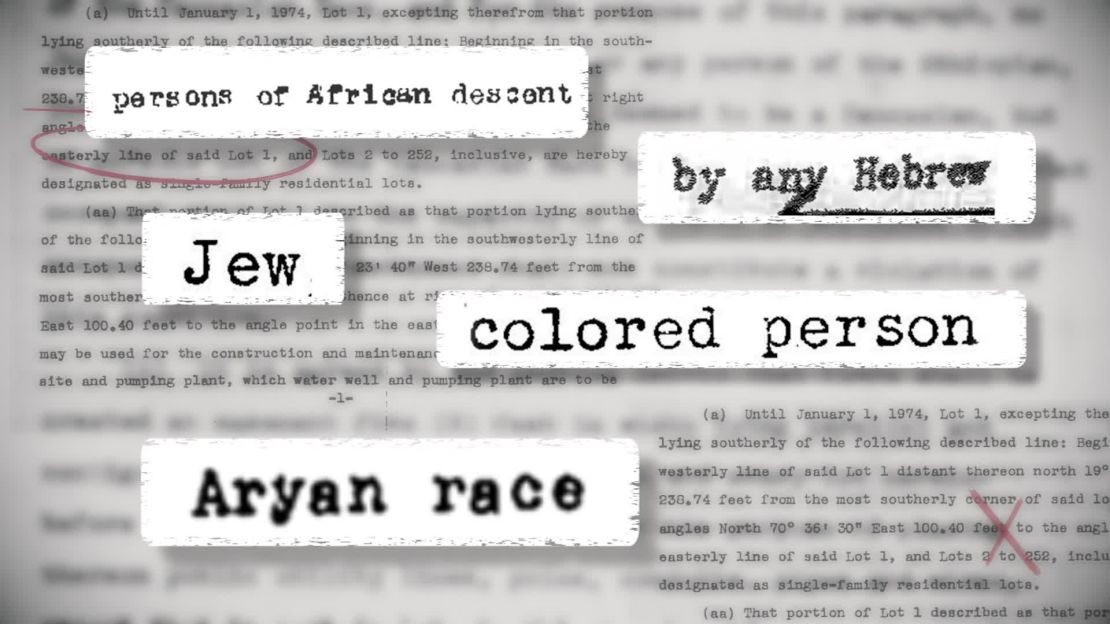

Black Americans were almost always excluded by these racial covenants. In many places, people of other ethnicities were barred as well.

“In Seattle and other West Coast cities, the racial mix of populations was pretty different,” history professor James Gregory of the University of Washington said. So, in Seattle’s Broadmoor neighborhood, for example, some deeds state that homes shall not be lived in by any “Hebrew or by any person of the Ethiopian, Malay or any Asiatic Race.”

One deed found by Mapping Prejudice in Minneapolis states, “No person of any race other than the Aryan race shall use or occupy any building or any lot.”

Language found in deeds by Mapping Segregation bars any person of the “Semitic Race,” spelling that out as “Armenians, Jews, Hebrews, Persians and Syrians.” That deed was written in 1958.

Other deeds across the country bar “Mongolians,” “Hindus,” “Chinese,” “Mexicans” and “Ethiopians,” which was used as a catchall for anyone with any ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa, Gregory said.

“They were trying to be legalistic about it,” said Gregory, who has mapped racial covenants in Seattle. “And so, instead of using what the jargon terms for different racial groups were, they tried to employ language from anthropology and race science.”

The federal government in 1934 endorsed such segregation by refusing to underwrite mortgages for homes unless a racial covenant was in place. Then in 1948, following activism from black Americans, the US Supreme Court unanimously ruled these covenants unenforceable.

Still, racial covenants continued to be written, enforced with threats of civil legal action.

The injustices of housing bias linger to this day

Finally, two decades later – in 1968 – the federal Fair Housing Act finally outlawed these covenants altogether.

But more than 50 years later, as the covenant language lingers in deeds across the nation, so, too, does the latent legacy it seeded from coast to coast.

“Housing is really the place where we have made the least progress in terms of civil rights,” said Hannah-Jones. “We often think that these laws and these practices were a long time ago. But they create an infrastructure of discrimination that goes forward.”

The many black and brown Americans whose ancestors were denied the right to live in affluent neighborhoods still feel the economic impact.

“That is the main way that Americans acquire wealth and save money,” said Delegard. “It’s the main way that they pass on assets to the next generation.”

Homes built under covenants in Minneapolis are still worth, on average, 20% more than the median value of homes in the city, Delegard and her colleagues found. And today, around 75% of white families there own the house they live in, while for black families, the figure is just 25%.

“The legacy of these restrictions, it’s demographic, in part, but it’s also profoundly material,” said Delegard’s colleague, Kevin Ehrman-Solberg.

In North Carolina, “there is still very little racial diversity in our neighborhood,” Reisinger said, adding that the racial covenant he found on his own home “made us think twice about it. And I can only imagine what an African American family would have felt.”

How to reckon with deeds’ racist language today

Projects to map these racist covenants are also now underway in places like Charlottesville, Virginia, Seattle and St. Louis. Many take their lead from the work done in Minneapolis by Mapping Prejudice.

“We’re the first project to map and identify all of the racial covenants for a given geographic area,” says Ehrman-Solberg who has developed, “optical character recognition, crowd-sourcing, a set of ancillary GIS and digital tools to at least partially automate this process.”

They have now applied for federal funding that, according to Delegard, “would make it possible for us to create a template, or a tool kit, so that any community across the country that wants to do this same kind of work, we would give them the tools.”

In Washington, DC, Shoenfeld first came across racial covenants while leading neighborhood heritage trails in the city, she said.

“Nobody seemed to be aware of how widespread this was,” she said. So, Shoenfeld and others began searching for the covenants, mapping them, hoping to raise awareness of the racist practices that shaped their city.

For those immersed in such study, there is hope this data can somehow be used to right those wrongs. Many do not want the racist language removed.

“Given the other things that covenants did that continue to impact cities and people, I don’t think that’s where the energy and money should go in addressing this legacy,” added Shoenfeld.

“My hope isn’t that we erase this language,” Delegard said. “My hope is that we use this language as a launch pad for making restitution.”

The California Association of Realtors, which had objected in 2008 to De La Torres’ bill, told CNN it now “stands ready to engage in the broader conversation about whether such covenants should be removed completely from a property’s history.”

For Hannah-Jones and others, that is the only solution.

“Absolutely, the language should be removed,” she said. “No one should have to procure housing and spend your money on a house and have in the deed racist policy that says someone like yourself is not allowed.”